Dark rides have been entertaining visitors since the beginning of the 20th century. Back then however, the concept of the ‘dark ride’ as we know it today was hardly developed. In fact, the first rides appearing all over the world that we would now call ‘dark rides’ were more like pioneering prototypes. The years around 1900 saw a wide range of technological developments, which in combination with the emergence of large-scale public entertainment led to the invention of various amusement rides. The world’s first dark rides were just a small part of this wide ongoing chain of inventions, where different inventions built upon one another to create the world’s first dark rides.

To understand the origin of this chain of inventions and developments, we need to go even further back in time. Already in the 18th century, two types of entertainment existed which included elements that would later be essential for the experience of the dark ride. One of these experiences was the Panorama: a large painting created on the inside of a cylindrical platform, giving visitors standing in the middle of the cylinder a 360° view of a specific site. In their nature, panoramas were the first experiences meant to immerse visitors into another world. This concept is still one of the basic elements of a dark ride, which intent to immerse visitors into a controlled environment and transport them to another place and/or time.

The second type of 18th century entertainment that could be regarded as a predecessor of the dark ride is the phantasmagoria or ‘ghost show’. These shows appeared on traveling fairgrounds, using the technique of the magic lantern (a primitive type of projector) to create a frightful and supernatural experience inside a dark indoor environment. “The phantasmagoria was a dynamic and exciting media format, in which the audience wasn’t moved physically but images were scaled and moved around them to great vertiginous effect” (Zika, 2021, p.56). Over time, the advent of electricity afforded safe and more controllable ways of illuminating such indoor experiences. The control over illumination and the atmosphere created by artificial light is one of the key elements that allowed for the development of the dark ride, and still is a major part in dark ride design.

Centralising entertainment

The first inventions leading to the world’s first dark rides would emerge by the end of the 19th century, partly based on the panoramas and phantasmagorias that already existed. The era in which the dark ride emerged was characterised by a major change in public entertainment in general, as large centralised entertainment venues started to appear from the second half of the 19th century. This was the era of urbanisation, when more and more people came to live in cities that soon became crowded. In these densely populated places, the idea of a park as a recreational place to step out of the busy city life gained popularity. This applied not only to traditional urban parks which were constructed in these years, with New York’s Central Park (1871) as major example, but also for venues including a higher degree of entertainment. With the large amount of people living in one single place, the potential market for entertainment sparked new, and larger, types of entertainment venues. Eventually, these were the locations where the first dark rides would emerge.

World’s Fairs

Before the rise of the first amusement parks, the most extravagant public entertainment areas were the World’s Fairs. Starting with the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, world fairs were held over irregular intervals in cities throughout the world. These fairs provided a showcase for state-of-the-art technologies and inventions from around the globe, drawing millions of visitors to their grounds for both education and entertainment. Especially interesting for the development of the amusement industry was the Chicago World’s Fair (also named Columbian Exposition) in 1893, which became known as the first expo to separate the area of amusement from the exhibition halls. The term ‘Midway’ was introduced for this area, which included several shows and rides, among them the world’s very first Ferris wheel. For future World’s Fairs, this idea of a midway remained (such as the San Francisco fair in 1894, launching the world’s first Haunted Swing) and the word Midway is commonplace in the amusement industry up to this day.

The rise of the Amusement Park

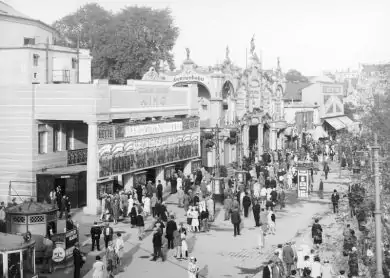

Though highly popular, these world fairs were expensive undertakings, requiring a major investment for a venue that only lasted one operating season. The success of these fairs inevitably sparked the rise of the amusement park as a permanent location to house similar attractions, with the midway of Chicago’s fair becoming the last step towards the creation of the first real amusement parks. The best-known examples of newly emerging amusement parks are Blackpool Pleasure Beach (U.K., 1896) and the series of amusement parks at Coney Island, New York (U.S.A., from 1895). Especially in the U.S.A., establishments similar to the widely popular parks at Coney Island were imitated in various locations to offer the newest kind of entertainment for visitors across the country.

In some cases, especially in Europe, amusement parks continued on the already existing venues: historical ‘pleasure gardens’, parks packed with entertainment that were generally found in European capitals, went along in the rise of the new phenomenon of the amusement park. Places like Prater (Vienna, Austria) and Tivoli Gardens (Copenhagen, Denmark) started adding amusement rides to their grounds, thus becoming true amusement parks as we would define them today.

The world’s first ‘dark ride’

The concept of the dark ride as we know today however, in all its complexity, did not pop up at once. It took a few steps by eager inventors to bring the first true dark ride to life. This process, in which inventions followed each other quickly, happened around 1900, along with the rapid development in the amusement industry in general.

The limits of technology

In those days however, technology was a major limiting factor in offering experiences that would eventually be called a dark ride. Already in the 1880’s, amusement rides emerged that offered a dark experience by driving a train through a mysterious tunnel. These cave train rides did not differ that much from regular trains, which in those days were driven by steam locomotives. The combination of a steam engine and an indoor ride was not a very convenient one, and it was not until the rise of the electrical engine that such experiences seriously took flight. The first electric motors enabled such trains to be propelled by clean electrical power, without filling the indoor sections with smoke. The technique of these engines however was not yet as advanced to be utilised for individual vehicles. This meant that a dark ride experience as we often see nowadays, with individual vehicles transporting a few people at a time through a building offering a degree of intimacy and mystery, was still out of reach.

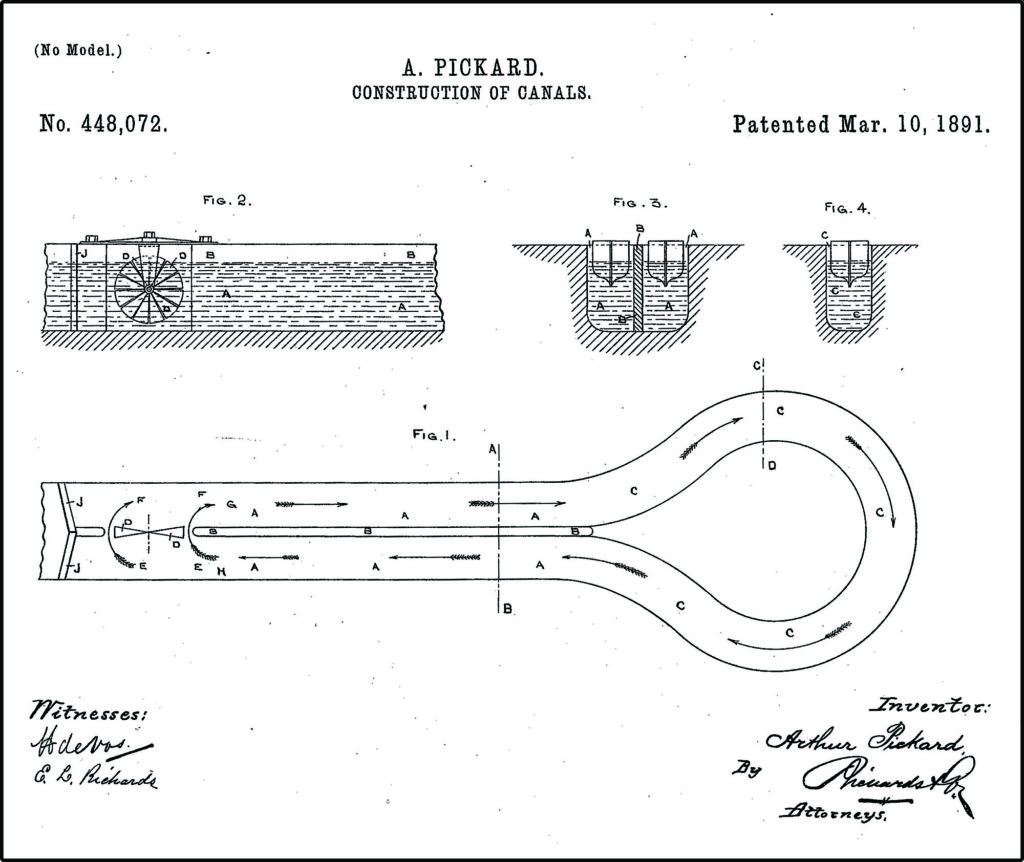

An alternative way to drive individual vehicles along a specified route was invented in 1891, when Arthur Pickard patented the invention of the ‘serpentine sluiceway’. Pickard operated his invention as an outdoor amusement ride in London. He did not use a track system, which required an engine for each vehicle: instead, he constructed a canal and invented a way to propel the water flow, which would take individual boats along the entire ride. The patent shows that the invention enabled a single engine to propel the water and create a continuous flow throughout the canal. This sluiceway was the first installation that could offer an individual experience for riders of a single vehicle, though Pickard only used the installation as an outdoor boat ride.

Coney Island’s ‘dark ride’

The ride by Arthur Pickard caught the attention of Paul Boyton, a showman at Coney Island, New York. Coney Island might be described as the birthplace of the amusement park: its seaside environment and good train connections to the city functioned as a major draw for visitors from the rapidly growing city of New York. The first amusement rides had emerged here since the 1870s, but the heydays of Coney Island were the years around 1900, when new developments and exciting rides were emerging every year to thrill the visitors. This started when Paul Boyton opened Sea Lion Park in 1895. Instead of operating some rides and charging admission for each of them, he fenced off his terrain and started charging an admission fee for the grounds. His park was a great success, with his famous shoot-the-chute-ride as major draw. However, the tumultuous economy at Coney Island rapidly saw the addition of a competing fenced-off park: In 1897, entrepreneur George Tilyou opened Steeplechase Park. The fierce competition brought Boyton in trouble: eventually, Sea Lion Park, the spark of the heydays of Coney Island, would only exist from 1895 to 1902.

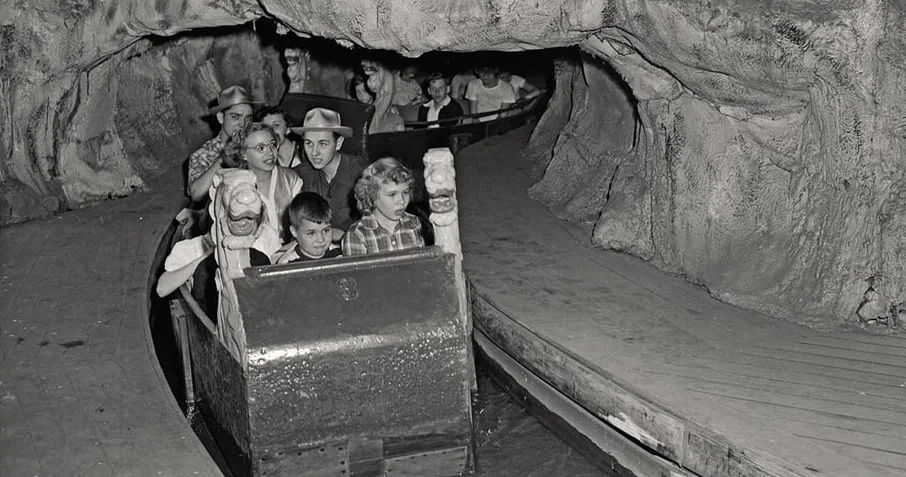

In its brief existence however, the park saw the introduction of the first indoor boat ride, inspired by Pickard’s invention. Instead of a quiet outdoor boat ride, like the original, Boyton built his installation indoors. This added a completely new element to the ride: pitch darkness. The ride was literally the first dark ride in the world. Riders were taken through a dark passage in two-passenger boats, which created an intimate atmosphere. The ride quickly became popular with young couples: in a time when physical contact between boys and girls was considered highly inappropriate, the ride offered a way to cling to one another in a public location without being seen. The name of this ride at Sea Lion Park is not known, but thanks to the nature of the ride it sparked the name Tunnel of Love for these kinds of attractions. The name is still used for old-fashioned scenic boat dark rides, which would quickly start to emerge based on the popular installation at Coney Island.

The Austrian cave ride

While the first dark rides emerged in America as boat rides, elsewhere in the world other inventions also led to the emergence of a specific type of dark ride. In Austria, a showman called Hugo Pilz continued on the idea of the cave train rides, and developed such a ride with an electrical powered train that took riders along scenic parts. In other words: he created (probably) the world’s first dark ride, considering the DRdb-definition that a dark ride should include scenes.

The location of his ride was Prater in the Austrian capital Vienna, one of the old ‘pleasure gardens’ which has been opened since 1766. Just like in Coney Island, the turn-of-the-century era was a heyday for Prater. In 1897 the Giant Vienna Wheel opened, inspired by the Ferris Wheel at the Chicago World’s Fair and currently the oldest existing Ferris wheel in the world.

Only one year after the opening of the wheel, in 1898, showman Hugo Pilz opened his brand new ride: Grottenbahn ‘Zum Walfisch’. The ride was built adjacent to Pilz’ restaurant Zum Walfisch (At the Whale), and consisted of a train riding through grottoes depicting different themes. The word ‘grottenbahn’ could be translated as ‘cave railway’, obviously referring to the cave-like setting in which the scenes (or grottoes) were presented. With its opening year in 1898, Grottenbahn ‘Zum Walfisch’ is probably the earliest true dark ride in the world, though sources on the actual opening dates of these historic rides often contradict one another. The ride consisted of a 600 metre long track, where electrically powered trains passed through 18 grottoes. These themed grottoes included depictions of the North Pole, the ‘witch kitchen’ and the ‘electrical wondercave’. Apart from the ride through the grottoes, a major draw of the attraction was its magnificent concert organ, playing excerpts from opera as supporting music along the ride. Reports from those days speak of many people, sometimes a hundred at a time, gathering around the ride to listen to the wonderful organ music.

Inspired by the Grottenbahn

The popularity of the Grottenbahn did not go unnoticed for the other showmen around the Prater grounds. One year after the opening of Pilz’ ride, the showmen Ludwig and Karl Pretscher opened their Grottenbahn ‘Zum Lindwurm’ (referring to a dragon-like creature from German mythology). This ride was rethemed in 1907, but unfortunately burned down in a major fire during the Vienna offensive in 1945. As for the Grottenbahn ‘Zum Walfisch’, no sources confirm that the ride has been demolished, rethemed or rebuilt anytime since 1898. The currently existing ‘Alt Wiener Grottenbahn’ is mentioned to be the park’s oldest Grottenbahn, which means it is probably the same ride as Hugo Pilz opened over a century ago. Unfortunately no clear confirmation is given, not even by the park itself, that this existing ride is indeed over 100 years old, leaving the fate of the original Grottenbahn ‘Zum Wahlfisch’ a mystery.

The influence of the Grottenbahn stretched even beyond Prater. Another installation opened in Linz, also in Austria. This ride, called Turmbahn am Pöstlingberg (Tower railway at Pöstling Hill), opened in 1906. It was located inside one of the defence towers of Fort Pöstlingsberg, a disused fortress on top of a hill a few kilometres from the city centre. It is unknown whether the ride included scenes, but we do know that a ride with the Turmbahn consisted of four laps: during the first three laps, the cave was lit in different colours for each lap. The most exciting part was the last lap, which took place in pitch darkness… almost pitch darkness, that is, since some light shone from a sign saying ‘no kissing’. Just like in Coney Island, where the darkness was an attraction on its own, informal contact between boys and girls was undesirable in Austria in those days. The Turmbahn saw the same fate as Grottenbahn ‘Zum Lindwurm‘, being destroyed in 1945 after a bombing. Since 1948, guests can enjoy a new grottenbahn at the top of Pöstling Hill, which is still operational and depicts scenes from fairy tales.

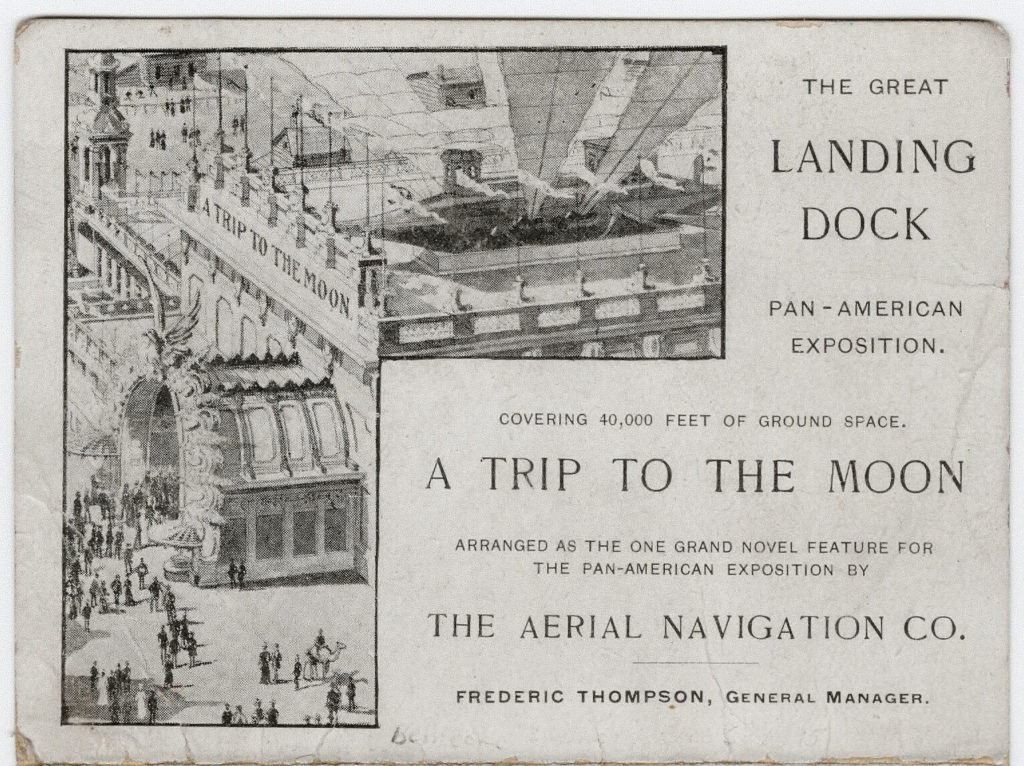

An immersive trip to the moon

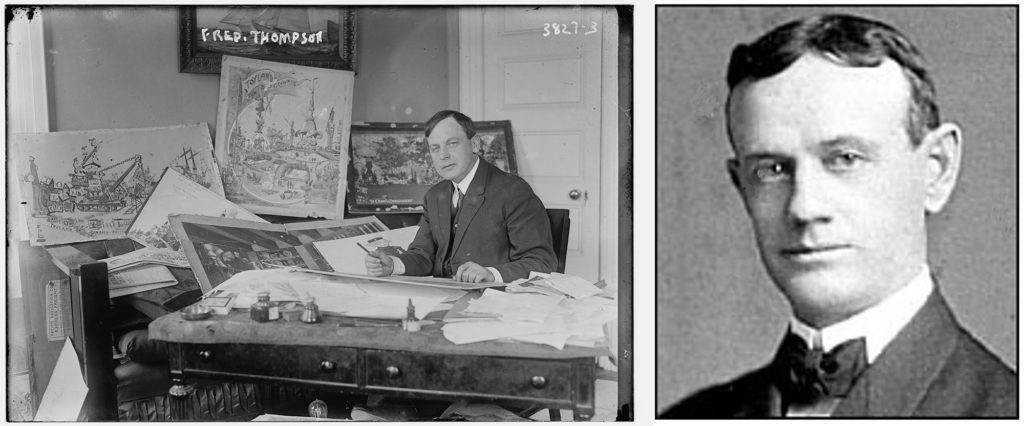

Back on the American side of the Atlantic, a one-of-a-kind experience appeared. In those days, the primitive dark rides mainly consisted of slow rides along scenes: entertaining, but not yet as immersive as we know the dark rides nowadays. However, in 1901, two men pioneered a ride that would be ground-breaking thanks to its immersive approach. These two men were Frederic Thompson and Elmer ‘Skip’ Dundy. Thompson was the creative mind of the two: trained as an architect, he ended up at the 1893 Chicago World Fair working several jobs. From there, he got into the business of expositions and entertainment, presenting the moving diorama ‘Darkness and Dawn’ at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha. Though already highly spectacular, that attraction was nothing close to his eventual masterpiece.

Dundy, on the other hand, was a showman with a feeling for business. He was well-educated and had great aptitude for financial matters, but his love for show business drove him into expositions as well. He created and ran two attractions for the 1898 expo In Omaha, but these turned out to be less popular than the other rides, especially the ‘Darkness and Dawn’-installation by Thompson. For the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, Dundy proposed his pirated version of Darkness and Dawn, using his business skills to outmanoeuvre Thompson. Eventually, Thompson and Dundy struck a deal for the 1901 expo, becoming business partners and sharing the profits of the four rides they ran together.

World’s first narrative-based amusement ride

Three out of these four rides would be similar to rides that either of the two had already presented at previous fairs, among them a version of Darkness and Dawn. The fourth ride was called A Trip to the Moon, and this was a truly special one. Thompson wanted to provide the visitors of his ride with an escape from everyday life, and was inspired by Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and by HG Wells’ The First Men in the Moon. He took a narrative approach like showmen had taken before, creating the idea to let the visitors board an airship and fly all the way to the moon. In those days, when flying already seemed like science-fiction to the people, the experience of a flight to the moon was nothing less than mind-blowing.

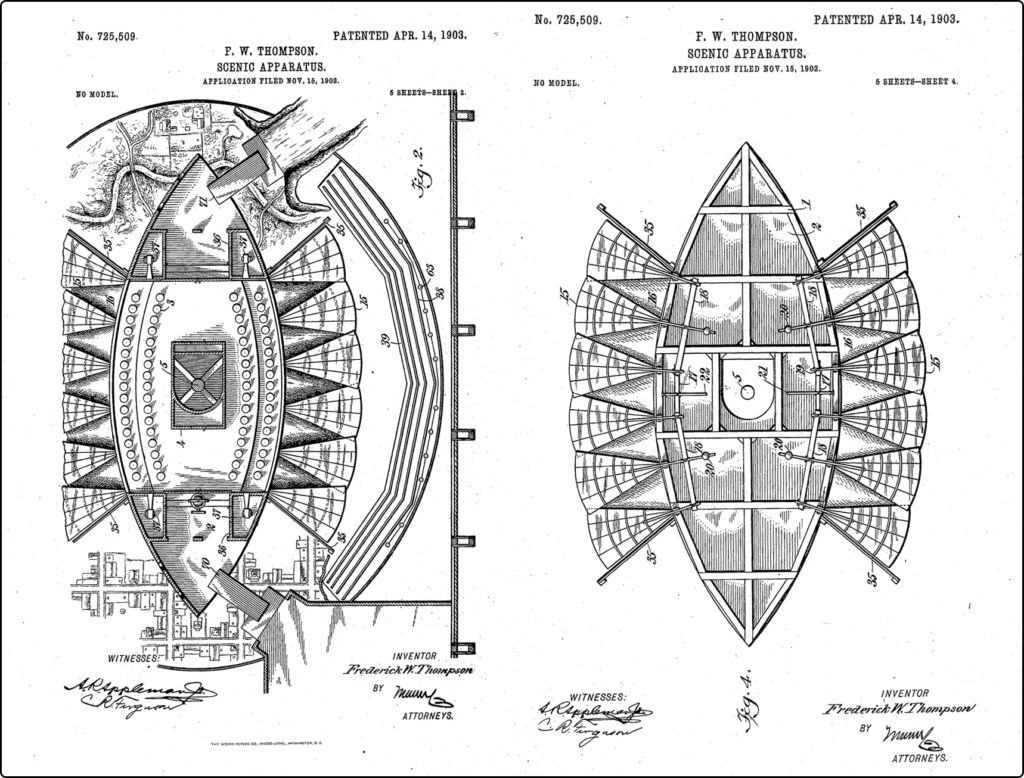

Thompson used a combination of mechanical effects, electric lights and projections to create an experience that no-one had ever seen before. He based his ride on the old technique of the panorama, the immersive paintings that were designed to completely surround the public. But instead of letting people watch the panorama at their own pace, Thompson designed a ride vehicle in the middle of the room. This ‘airship’, which was called Luna, was suspended from the ceiling by a few central steel cables, permitting the ship to rock and swing lightly. Riders would enter the immense room over a ramp, leading to the ride vehicle that was floating in the space. The vessel had the shape of a row boat, but was equipped with large wings at the place where oars would regularly have been, just below where the riders sat.

Once riders took their seats, with a maximum of 30 per ride, the panorama surrounding the vessel would come to life: it was a giant cyclorama, operating as a gigantic scroll passing around the riders. In combination with the movement of the cyclorama, fans would create wind and the vessel would start to shake and heave, creating a convincing feeling of movement. As the scroll went by, people would initially see Niagara Falls, then the city of Buffalo seen from the sky, and eventually the earth’s surface, as if they had truly taken off for a flight in outer space. Moreover, Thompson installed a series of stereopticons both above and below the visitors, out of sight thanks to the ship’s large wings. Stereopticons were projectors that were able to fade between projected images, which allowed Thompson to project clouds as if they were gliding past. All stereopticons together allowed for a 360° projection on the panorama, which Thompson used in combination with light effects for the creation of, for example, a thunderstorm. Eventually, riders would reach the moon, leave the vessel and walk into a lunar cavern made out of plaster, where employees dressed like inhabitants of the moon (which Thompson called Selenites) sold souvenirs and special food. From here, riders would enter the palace of the Man in the Moon for a final dance show, and eventually leave the experience.

A Trip to the Moon was completely different from other experiences in these days, by way of its focus on conjuring up very specific atmospheric illusions. Thompson used a range of techniques, all of which were already known, and deployed them in such a way that they created new spectacles. Combining these illusions enabled Thompson to create a convincing experience of a trip to the moon, an approach that no other showman had taken at that point. Technically speaking, A Trip to the Moon is not exactly a dark ride. In fact, it is a show ride: it is the world’s first motion simulator, in some way the predecessor of the immersive tunnel. But the way in which the combination of scenery, effects and a moving vehicle was used to create a coherent narrative-based experience also characterises the experience of a dark ride. That is why A Trip to the Moon can definitely be regarded as a major step in the development of the first dark rides in the world.

The success of Thompson and Dundy

A Trip to the Moon was a ride of a scale that had never been seen before. Thompson and Dundy spent a staggering $84.000 to build the ride, over $2M in today’s money. Riders were eager to pay $0,50 (around $16 nowadays) to experience the flight to the moon themselves, twice the price of other rides at the expo. The ride required 20 employees to operate and another 200 actors for the show and to play the Selenites. Despite the large investment and operational costs, the ride was very profitable, partly thanks to the merchandise sold in the moon cavern. A Trip to the Moon was not only the first truly immersive amusement ride, it also paved the way for merchandising in amusement parks. Dundy’s feeling for business clearly did not let him down on this occasion.

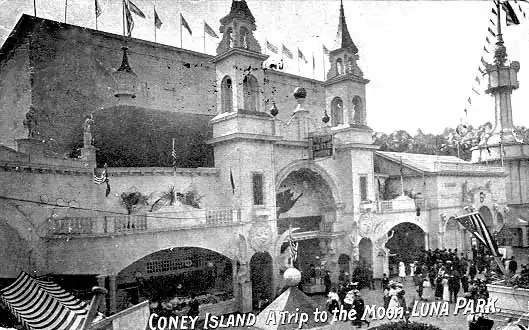

The success of A Trip to the Moon did not go unnoticed for George Tilyou, the entrepreneur who opened Steeplechase Park at Coney Island. In his fierce competition with Sea Lion Park, he was always looking for new experiences to draw visitors. Tilyou invited Thompson and Dundy to transport their attraction to his park, enabling them to continue the profitable operation of the ride after the fair had ended. A few changes were made: the aerial views of Buffalo were replaced with Manhattan and the vessel was adapted to allow for higher capacity, after which it was renamed ‘Luna III’. The ride operated in Steeplechase Park during 1902, but the duo were unhappy with the amount of profit they had to share with Tilyou. Thompson and Dundy planned to move the ride away after the season and bought the plot of Sea Lion Park from Paul Boyton, constructing a brand new park on the site and moving A Trip to the Moon to the new location for the 1903 season. They decided to name the park after their spaceship: ‘Luna Park’. Many parks throughout history have been named after this famous amusement park, which indirectly means that the world’s very first narrative-based ride is still honoured in amusement park names around the globe. After the death of Dundy in 1907, Thompson filed for bankruptcy in 1912 and was forced to hand over Luna Park to his creditors. It is not known whether A Trip to the Moon was still operational during this time. Nevertheless, the ride made history since it was ground-breaking in its scale, immersiveness and commercial exploitation, which would not be seen again to this extent for more than fifty years.

The scenic boat ride

The location where A Trip to the Moon spent its last years was the same as the location of the world’s first ‘dark ride’, as was mentioned earlier. This Tunnel of Love already proved a success, but it was not until such rides were extended with scenes that the dark boat ride truly took off. The ride type that emerged, which would be called Tunnel of Love, Old Mill or River Caves, was the first type of dark ride that spread around the globe. From a one-of-a-kind spectacle, the dark ride was rapidly evolving into a format. This created room for parks to adapt the dark ride to their own purpose and tailor them to their own public, starting an “evolution of different styles of the ride” as Joel Zika (2021) calls it.

The Old Mill

The first adaption of the Tunnel of Love opened in the same year as A Trip to the Moon in Kennywood, recently opened amusement park just outside Pittsburgh, PA. Just like Coney Island, Kennywood is a so-called ‘trolley park’: a park located at the end of a tramway which allowed easy access for people from the nearby city. Kennywood opened in 1899 and rapidly expanded by adding amusement rides, The Old Mill being the first major ride in 1901 (their first roller coaster would open just one year later).

The design of the Old Mill took the ride system from the Tunnel of Love at Coney Island. For creating the water current in the canal, Kennywood’s Old Mill used a large paddle wheel, an idea inspired by the many water mills that could be found in the area in which the park is located. Continuing on the concept of the water mill, the park built the whole ride building as if it was a dilapidated sawmill. Moreover, the boats were originally shaped like logs, representing the actual logs transported over the river towards the real sawmills just around the corner. The idea of shaping boats after floating logs seems obvious nowadays, but in 1901 the creation of a coherent narrative which explained the looks of the ride system (paddle wheel), vehicles (logs) and show building (old mill) was truly unique. Moreover, the park derived the idea of the theme from its own surroundings, an example of a tailor-made version of the ride created to suit the public and the city where it was located. This way of thinking was yet another step towards creating immersively themed rides, where every part of the ride is meant to contribute to a coherent story.

Little is known about the exact interior of the Old Mill in its very first operating years. Reports state that the ride featured “gorgeous grottoes or musical caves”, all of which were lit by state-of-the-art electric lights. The ride consisted probably of both indoor and outdoor sections, leading around and through the Old Mill building. Ever since first opening, the ride has seen no less than 11 rethemes, of which the first occurred just five years into operation. Apart from rethemes, the ride suffered from a major fire in 1911. The continuous development of the ride makes it hard to trace back the original components and those that were added later. In the beginning of the 1920s, the ride lost one of its key storytelling elements when new boats were installed that were no longer log-themed (as shown in the picture). Regardless of all changes, the ride is still operational today: better still, Kennywood recently rethemed the ride once more to honour the original Old Mill. This latest version, logically called The Old Mill, has been entertaining visitors since 2020.

Boat ride to Hell

The scenic boat ride soon developed into a format which parks adapted for their own public, and it would not take too long before an installation opened at Coney Island. This ‘Hell Gate’ was one of the most notorious installations of a scenic boat ride. The ride could be found in Dreamland, the third amusement park at Coney Island (beside Steeplechase Park and Luna Park) that opened in 1904. Hell Gate was the star attraction of Dreamland’s second season, opening in 1905. The ride constituted a large investment and was the ultimate effort to one-up Luna Park and its immersive experiences.

Visitors of Dreamland could hardly miss Hell Gate, a large building topped by none other than Satan himself looming over the park. Underneath the statue, a large open room showed the first section of the ride. Guests could watch riders boarding open boats and then descending along an ever-narrowing 20-metre whirlpool swirling toward the centre. The contents of the rest of the ride have been well-described by Theodore Waters in the July 8, 1905 issue of Harper’s Weekly: “The ‘pool’ is merely a spiral trough made of wood and iron, through which the water carries the boats to the centre, where the slope suddenly dips and allows them to slip beneath the outer rims of the spiral into a subterranean channel which follows a tortuous course under the building. There are scenes… intended to corroborate the popular conception of the Earth’s interior. […] By the time the spectators above are beginning to wonder what has happened to the boat, the passengers have had a surfeit of subterranean horrors, and are shot up through one side of the pool to the surface.”

Hell Gate stands out not only for its crowd-drawing whirlpool, adding an element of thrill and mystery to the ride, but also for its theme. Around 1900, in the era of technological developments that enabled people to travel further and more easily than ever before, most dark rides based their theme on the idea of travel. For both Prater’s Grottenbahn and Kennywood’s Old Mill, early scenes are known to have depicted famous places on earth. The narrative of A Trip to the Moon took the idea of travelling even one level higher – literally. Hell Gate, however, based its theme on the religious concept of Hell. Interestingly enough, this idea was partly based on economic considerations since in New York only parks including ‘religious entertainment’ were allowed to open on Sundays. Sadly the renowned ride only lasted six years: in 1911 Hell Gate was destroyed in a huge fire, which fortunately did not result in any casualties. Ironically such a giant Inferno was probably the most appropriate way to destroy the boat ride to Hell.

The English River Caves

An adaptation of the dark boat ride that has had a significantly longer life than the Hell Gate can still be found at Blackpool Pleasure Beach. This famous park could be referred to as the English Coney Island, being an amusement park with a successful start around the turn of the century and having a significant impact on the rise of the amusement park industry in general. Just like at Coney Island, the location on the seashore and at the end of a railway line started to draw lots of tourists to the town of Blackpool, which inevitably inspired entrepreneurs to establish entertainment venues to take their share of visitors. Two of these were William George Bean and John Outhwaite, business partners who in 1896 bought a plot of land at the very end of the already famous Blackpool Boardwalk and established Blackpool Pleasure Beach. Even today, the park is still owned by the family of Bean, with the current managing director being his great-granddaughter Amanda Thompson.

Although Blackpool Pleasure Beach was founded in 1896, the first major amusement ride did not appear until 1904 when ‘Sir Hiram Maxim’s Captive Flying Machine’ opened, a swing ride designed by the British inventor of the same name, which is still the oldest operating ride in the park. One year later, the park opened The River Caves of the World: an immense dark boat ride in the same vein as the Old Mill in Kennywood. Riders would board a boat and be transported into a fake mountain, which was visible from most of the park’s grounds. After their tour through the mysterious River Caves, riders would exit the mountain with a splash. The theme of the River Caves has been very consistent throughout its existence: even though changes to the ride’s interior were made, the narrative has always centred on journeys to far flung lands, just like in the majority of other rides of the same era.

Rides like the River Caves created a format for experiencing travel to other countries through a singular location based attraction, making the experience of such travels available to a larger public. In 1977 park director Geoffrey Thompson described a similar idea behind his addition of a replica of the temples of Angkor Wat in Cambodia to the ride: “The temples are no longer on view to the Western World since the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia so you could say that we are offering people the only chance they will get to see them” (Quoted in Zika, 2021). Just like the Old Mill, the River Caves served the public desire to travel through 360-degree environments and have the feeling of being transported somewhere else, somewhere out of their everyday life. In that sense, these dark rides are still inspired by the same idea that sparked the creation of the panorama paintings in the 18th Century, which marked the start of our story.

The dark ride at the brink of the First World War

The River Caves at Blackpool Pleasure Beach would definitely not be the last installation of an Old Mill-type of ride. In the following years, similar rides appeared in (amongst others) Rocky Glen Park (PA, U.S.A.), Luna Park at Coney Island and Pleasureland Southport (U.K.). Clearly, the dark ride has risen to a ride format in the 10 years since Paul Boyton launched his Tunnel of Love. In particular, the Tunnel of Love/Old Mill-rides rapidly spread around the world, taking on different forms in each park to match the local desires. Within Austria, the Grottenbahn saw a similar development, becoming a ride format which was copied multiple times.

The development of this ride format occurred over a rather short period of time from 1890 to 1905. This development was built upon inventions that had their roots in early entertainment, like panoramas and phantasmagorias. Some inventions, like the serpentine sluiceway, would cause a chain of rides to continue on its idea, while others would be so ground-breaking that no-one was capable of building a similar experience (A Trip to the Moon). But let us not forget that this series of inventions took place in a time when amusement rides in all kinds of formats were developed rapidly. The amusement industry grew astonishingly fast in those days, and dark rides were just one product of that. Some developments which initially strived for a similar experience would take another path and become a whole different type of ride – such as the gravity powered ‘Scenic Railway’, which originally included scenes, but turned into a scene-less version of the roller coaster.

Just as quickly as the development of the dark ride had started, so rapidly did it demise after 1905. Technology was still a problematic limiting factor in the creation of individual indoor experiences. With the train ride, the canal ride and the gravity ride being developed as a way to transport visitors along scenes, most of the possibilities were investigated. By the time of the outbreak of the First World War, no new inventions were made regarding dark rides, though new installations of Old Mill-rides kept popping up. It would take until the late 1920’s before the world of dark rides was shaken up again, when technology finally allowed for electrically driven individual cars. But that is a story for another time.

© Dark Ride Database

Article by Luc

Research by Alan and Luc

We would like to thank Joel Zika (The Dark Ride Project) for his advice on this article

References

- Barber, X. (1989). “Phantasmagorical Wonders: The Magic Lantern Ghost Show in Nineteenth-Century America” Film History, 3(2), 73-86

- Dark Attraction & Funhouse Enthusiasts: http://www.dafe.org/articles/darkrides/darkSideOfKennywood.html

- Defunctland: The History of Coney Island: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7C5kxkBPhpE

- DÖW (Dokumentationsarchiv des Österreichischen Widerstandes). Archived letter by Franz West, dated February 1934. https://www.doew.at/erinnern/biographien/erzaehlte-geschichte/februar-1934/franz-west-jetzt-muss-man-was-machen

- Kwaitek, B. (1995) The Dark Ride, published thesis (MSc), Western Kentucky University

- Mental Floss: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/626271/hell-gate-coney-island-dreamland-water-ride

- Nye, R.B. (1981) “Eight Ways of Looking at an Amusement Park” The Journal of Popular Culture 15 (1) pp. 63-75

- Silverman, S.M. (2019) The Amusement Park: 900 years of thrills and spills, and the dreamers and schemers who built them, New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

- Theme Park Insider: https://www.themeparkinsider.com/flume/201302/3378/

- Wien Geschichte Wiki: https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Grottenbahn

- Zika, J. (2021) The Historic Dark Ride: Reimagined for virtual experience, PHD research, Swinburne University

- Wikipedia:

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grottenbahn

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linzer_Grottenbahn

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Mill_(ride)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Trip_to_the_Moon_(attraction)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederic_Thompson

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elmer_%22Skip%22_Dundy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackpool_Pleasure_Beach